Doctors: Why PPE is the least effective way of protecting yourself from COVID-19

This article is written by Abeyna Bubbers-Jones. A London based Occupational Health Consultant and Founder of Medic Footprints. Aimed at doctors working on the front line of the COVID-19 outbreak, but relevant to everyone! Please also note it is designed…

This article is written by Abeyna Bubbers-Jones. A London based Occupational Health Consultant and Founder of Medic Footprints. Aimed at doctors working on the front line of the COVID-19 outbreak, but relevant to everyone!

Please also note it is designed to introduce you to the principles associated with exposure control. Please apply them to your particular situation – especially if examples given are not directly relevant to your clinical practice.

With the emerging coronavirus crisis in Europe – more and more doctors are finding themselves at the clinical frontline with little or no protection from exposure.

With several doctors in the media succumbing to the virus such as Dr. Li Wenliang in Wuhan and GP & Medical Chief Dr. Roberto Stella in Italy, no wonder us medics are increasingly anxious about the situation and how this will impact on us?

We’re used to being exposed to infectious diseases at work.. right?

Although exposure to contagious diseases is a standard occupational hazard associated with being a doctor or healthcare worker; in most cases the hazard is well-known and the risks are effectively managed with standardised procedures and risk assessments.

It’s also the law for employers to make sure they do this – check out what COSHH means.

In this global crisis however, relatively little is known about the nature of the hazard; in this case coronavirus.

And with relatively little understanding of the true nature of how it behaves in relation to humans, it is difficult to effectively and safely manage the full risks of exposure.

We’re at a time whereby doctors and other healthcare workers are in many ways expected to ‘take one for the team’ and put themselves in the firing line. There is even talk of pulling retired healthcare workers back into the NHS to assist with the strain; many of these are likely older and possibly vulnerable to infection due to other co-morbidities.

Protection of staff members is a secondary consideration in this case.

So what can we do for ourselves?

You may be reading this for any of the following reasons:

– You’re on the clinical frontline with no or little PPE

– You’re a relative or close relation of a doctor / healthcare worker (HCW) on the clinical frontline and worried about their and your exposure

– You’re thinking about coming out of retirement to join the cause and worried about your exposure

– You’re generally anxious about everything related to the crisis

Whichever the reason, it’s important you’re consciously aware of the following to ensure you’re informed about your behaviours and decision making related to your work or exposure during the outbreak.

Difference between Hazard and Risk?

It’s important to understand for the purposes of this article that

Hazard = something which has the potential to cause harm

Risk = chances of that harm happening

e.g. driving in your car at over 70 miles per hour on a country lane is a hazardous activity that has a high risk of injury to yourself or others

What is PPE exactly?

PPE is an acronym for Personal Protective Equipment.

This includes items that can be personally worn and managed by yourself to reduce the risk of exposure to a hazard such as the coronavirus. This includes gloves, masks, gowns etc.

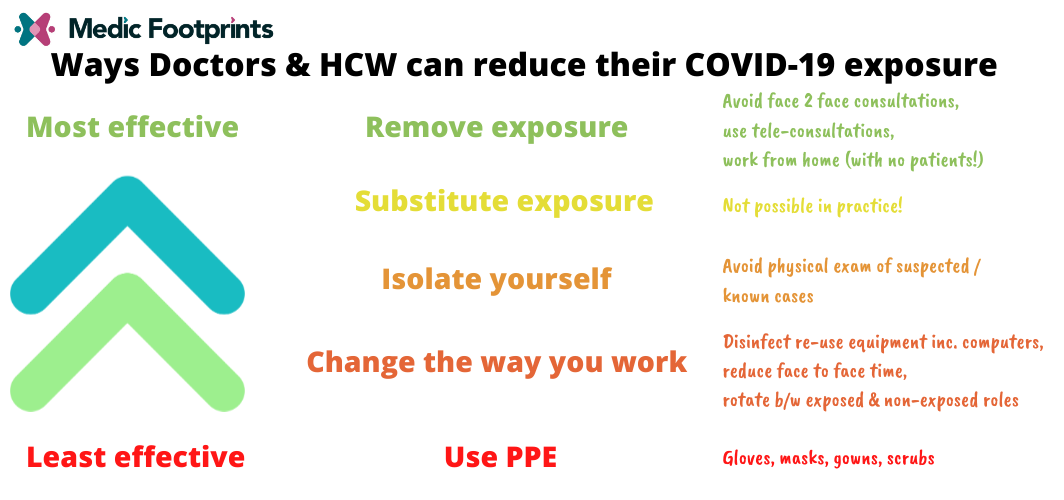

When OH or anybody in a workplace setting review how to best reduce exposure to a known hazard, we refer to a hierarchy of control.

Below is how this relates to your exposure to COVID-19.

The most effective measure of managing the exposure is by completely avoiding or eliminating it.

The least effective measure is what everyone is obsessed about – PPE.

Why is PPE the least effective?

One of the main reasons is that PPE is only as effective as it’s correct use in the event of an exposure. This relies on us as individuals using it correctly.

Even when used correctly, no form of PPE is 100% effective.

PPE users need to be educated and trained in it’s use – and regular auditing is needed to ensure these good practices are sustained day to day. Most PPE is relatively uncomfortable which can result in inadvertent misuse and potential cross-contamination leading to an increased risk of exposure.

Example problems with..

Masks:

Users can get too hot, can interfere with other PPE, can slide around if poorly fitted, no access to nose, makes it difficult to work, not great with beards (!)

Think about the number of times you may want to touch your face with your hands to adjust the mask.

Gloves:

Can cause sweating and contribute towards dermatitis, allergic or contact dermatitis to chemicals to size, finding gloves that fit, cross contamination on donning and removal.

Gowns:

Can interfere with other PPE and work practices, sizing issues, cross contamination

It’s also important to be aware that PPE is seen as a last resort measure, and should only be implemented when all the more effective control measures (see image above) has been exhausted.

Practical things you can do to protect yourself as a doctor at work

These are written in relation to the hierarchy of control above.

MOST EFFECTIVE: Avoid all face to face working

This option can be employed by doctors working in a primary or non-acute setting.

Phones, videoconferencing or even messaging can be used to assess patients remotely.

In practice, many primary care practitioners can do this relatively easily as they already have systems in place for telephone or video consultation, or may be working for company that provides remote online services like Doctor Care Anywhere.

Although as of writing, formal arrangements for doing this have not been explicitly advised by health authorities, it is important to remember you are still within your rights to take precautionary measures as you see fit as part of your own risk assessment. Depending on your employment situation and concerns you may have about exposure at work, it is best to discuss your needs with your employer.

If you’re coming out of retirement to help the cause – consider whether you can avoid any face to face work or explore helping in other ways. Could you put your clinical acumen to good use without physical contact with patients?

If you have underlying health conditions and/or in the older age demographic consider that you are particularly vulnerable to developing a severe illness if caught.

Avoid direct contact with patients with cold or flu like symptoms

If you do have to physically see patients, consider avoiding direct touch and employ a reasonable level of distancing where possible. With these kind of patients, it’s unlikely your physical exam will significantly aid your diagnosis above and beyond objective investigations and tests.

Reduce exposure time

If you are seeing and examining patients, can you reduce your exposure time to potential cases? Examples of this may include:

- Rotating shifts and tasks from no/low risk exposure to high risk exposure activities. Can you focus on triage/admin for part of your shift and see patients for the rest?

- Less time in physical contact with your patient

- Consider consultation in larger rooms

- Is the ventilation of your room optimal? Even if you opened the window?

- Fewer or shorter shifts on the clinical front line where possible

These are dependent on your work arrangements and will require cooperation of your colleagues or department, but worth serious consideration.

Minimise equipment re-use

Do you need to use your personal stethoscope and other items as regularly as you do?

If so make sure you have a reliable way of cleaning it effectively after each use

Consider increasing use of disposable items

Avoid sharing items like pens and paper – especially with your patients. Keep as digital as possible

Hand washing

This likely drilled in already but be aware that overly washing hands can lead to an already common outcome of occupational dermatitis and skin breaches can increase the risk of you catching or harbouring infections

The answer to this?

- Avoid the need to hand wash as regularly by avoiding face to face / front line clinical contact altogether (if you can).

- If you do have physical contact/exposure with patients, hand-wash regularly but not excessively. (OCD type behaviours can develop in times like these!)

- Use moisturiser after every wash. Dermol 500 is a great soap substitute and moisturiser and can be easily requested if you’re prone to dermatitis or otherwise. Especially in the NHS.

- Remember, if you genuinely need it for work, your employer should be responsible procuring it or a reasonable alternative for you.

LEAST EFFECTIVE: PPE

Ok – so we finally got here.

The thing people talk the most about is actually the least effective way of protecting yourself from COVID, however don’t forget that it does have it’s place and can be an effective control if used correctly.

Some tips for PPE include:

- Use disposable single use PPE as a preference

- Ensure you read / familiarise yourself with the instructions on how to best use your PPE because cross contamination is very easy to do

- Understand it’s limitations (see earlier)

Remember PPE is only as effective as its use and only works optimally when you’ve implemented and/or exhausted all the more effective ways of avoiding COVID-19 exposure.

Take home points

- PPE is the least effective way of protecting yourself from COVID-19

- No PPE? Don’t stress too much – make sure you’ve covered the more effective ways of reducing your exposure first.

- Discuss more effective ways of reducing exposure with your team and employer

- If you don’t feel safe – don’t do it!

Check out the UK government risk assessment for Healthcare workers on Infection Prevention and Control for COVID-19.

Abeyna Bubbers-Jones

Latest posts by Abeyna Bubbers-Jones (see all)

- How to express your interest for job opportunities on the Medic Footprints website - 31st December 2021

- Books for Doctors in Career Change: The Ultimate List - 5th May 2020

- Strategy Consulting Webinar with Dr. Rohit Chitkara from PWC UK - 29th April 2020